Introducing Charpentier and La Sainte Chapelle

In conjunction with our upcoming live recording of Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Missa Assumpta est Maria, Edward Higginbottom explores the relationships between Charpentier, his musicians, and La Sainte Chapelle..

Those of you who have visited La Sainte Chapelle in the heart of Paris will know what I mean. Those who haven’t, can (in post-Covid times ) pop their head round the door of Exeter College Chapel. But it has to be said, the French version is the real McCoy. The upper floor of the Chapel is a single space of exaggerated height whose walls are there primarily to support the most stunning expanse of 13th-century stained glass in all France. When the sun pours in, being inside this space, topped with its bespangled ceiling and framed by its boldly coloured stonework and friezes, is an unparalleled experience. One could well believe that heaven had flung open its portals.

La Sainte-Chapelle, Paris

It was a royal chapel, built by Louis IX to house relics of the Cross, and set in the Royal residence of the day, the Palais de la Cité. Later, the kings of France moved to other quarters, notably the Louvre and then Versailles, by which time – the end of the 17th century – Marc-Antoine Charpentier found himself walking up the staircase to the upper chapel to take charge of his musicians. His employers, having previously been Marie of Lorraine (Mlle de Guise), and then the Jesuits in the rue de St Antoine, were now the canons of La Sainte Chapelle, a powerful and wealthy body of ecclesiastics whose ambition for their liturgy was equal to the splendour of their surroundings.

We are now in the final years of Charpentier’s life. His appointment in 1698 as Maître de Chapelle was to be his last. Indeed, it crowned his career, awarding him rank and prestige which earlier circumstances had withheld. And it was here, amid the grandeur of this unique Gothic building, that he first performed his Missa Assumpta est Maria.

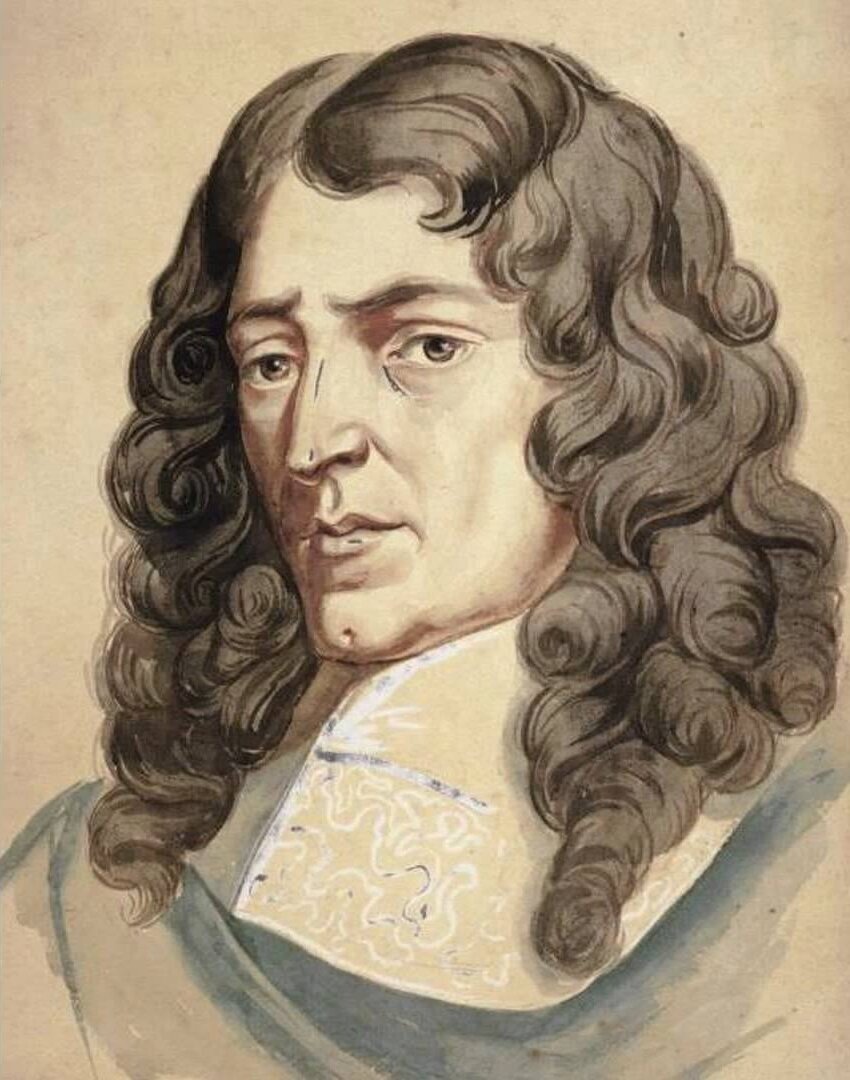

Portrait presumed to be of Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Artist Unknown

Charpentier’s music, numbering some 550 works, is largely sacred, and almost wholly conserved in a large autograph collection called Les Meslanges, numbering 28 volumes. Dating the materials within these volumes is not as easy as beginning with the first and ending with the last, not least because each volume comprises various cahiers assembled in a somewhat haphazard fashion. However, Catherine Cessac, Charpentier’s biographer, confidently assigns the Missa Assumpta est Maria to 1702, just two years prior to the composer’s death. And we may safely assign its first performance to 15 August that year, the Feast of the Assumption of the BVM.

This Marian feast was then, and remained so, the most important of the Marian feasts, notwithstanding its dubious scriptural standing. Whereas, for example, the feasts of the Annunciation and the Nativity of the BVM were lodged in biblical narrative, none existed for the crowning of Mary as the Queen of Heaven. But one can understand this flight of imagination: it was the most focused way of venerating Our Lady, permitting, as a feast of the first class, the right level of ceremony. We might liken it to the Feast of Christ the King, but for Mary. There is no doubt that Charpentier saw the feast as meriting a special effort on his part. And we can fairly describe the Missa Assumpta est Maria as one of his most accomplished works, certainly the most remarkable of his mass settings. To my way of thinking, La Sainte Chapelle has much to do with that, and I’ll tell you why in my next blog.

Instruments of Time and Truth’s live recording of Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Missa Assumpta est Maria will be released soon. In the meantime, you can watch the ensemble’s performance of the Motet Annuntiate Superi and Sonate a 8, directed by Edward Higginbottom, below.